June is National Indigenous History Month, a time to recognize and celebrate the rich history, tradition and diversity of Canada’s First Nations, Inuit and Métis people. This month is also an opportunity to honour the stories, achievements and resilience of Indigenous Peoples.

In early childhood education, post-secondary programs that partner with Indigenous Institutes provide a way of obtaining an ECE diploma by weaving academics with the cultural richness of Indigenous knowledge, values, community and traditions.

One such institute is First Nations Technical Institute (FNTI) an Indigenous-owned and -governed post-secondary institute, which offers an ECE program in partnership with Canadore College.

Cecil E. Isaac Jr., who is from the Mshiikenh indoodem (Turtle Clan), is a Cultural Advisor (CA) at FNTI and has been integral in implementing Indigenous Learning Outcomes (ILOs) into FNTI’s framework of teaching.

Born in Chatham Ontario, raised on Bkejwanong Territory, Walpole Island, Ontario, Cecil comes from a lineage that embraced and shared rich cultural teachings and who were survivors of the Residential school era. Cecil has been instrumental in revitalizing ceremonies within his family and community. We spoke to Cecil to learn more about Indigenous values and his experiences sharing the wisdom and knowledge of his culture with ECE students at FNTI and with young children in the community.

(Note to readers: Acknowledging the multitude of unique histories, languages, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs that exist among Indigenous Peoples, the following is not intended to represent the ways of knowing and being of all Indigenous Peoples).

Indigenous Learning Outcomes (ILOs)

Created by the Negahneewin Council, Indigenous Learning Outcomes (ILOs) allow for Indigenous knowledge to be embedded into the program curricula of colleges and institutes, including FNTI and its ECE program. Across seven ILOs, they look at: how colonization affected, and continues to affect, Indigenous communities; the connection between land and identity in Indigenous societies; strategies for reconciling Indigenous and Canadian relations; racism against Indigenous people; and approaches for engaging Indigenous community partners.

“ILOs ensure Indigenous ways of being are communicated to the very impressionable – our little people, our newborns – and how important it is to understand those cultural things,” says Cecil. “ILOs were implemented to take a deeper look into the Indigenous culture – the sacred bundles, the teachings, ways of life.”

Education as medicine

Education is valued as a powerful tool for healing. Education rooted in Indigenous knowledge allows Indigenous Peoples to reclaim and connect to the wisdom of their ancestors, revitalize language, address historical trauma, promote an understanding of reconciliation and foster pride in Indigeneity.

“Education is healing. Education is love, which is one of our values, our Grandfather Teachings,” says Cecil. “If you look at education as love and as healing, they can also be translated to education as medicine, and therefore educators are medicine to those young people. Our little ones, our future. It is very important to allow our little spirits to become involved.”

An Indigenous approach to education takes a holistic view, developing the body, mind, heart and spirit of learners. Classes in FNTI’s two-year ECE program may begin, for example, with a Knowledge Keeper doing a smudge ceremony or drum ceremony. Each semester, cultural activities are completed by the learners, such as a rattle ceremony or unburdening ceremonies, all guided by cultural advisors like Cecil. ECE students learn the significance of each activity and how it is important for the children they will be caring for and supporting out in community.

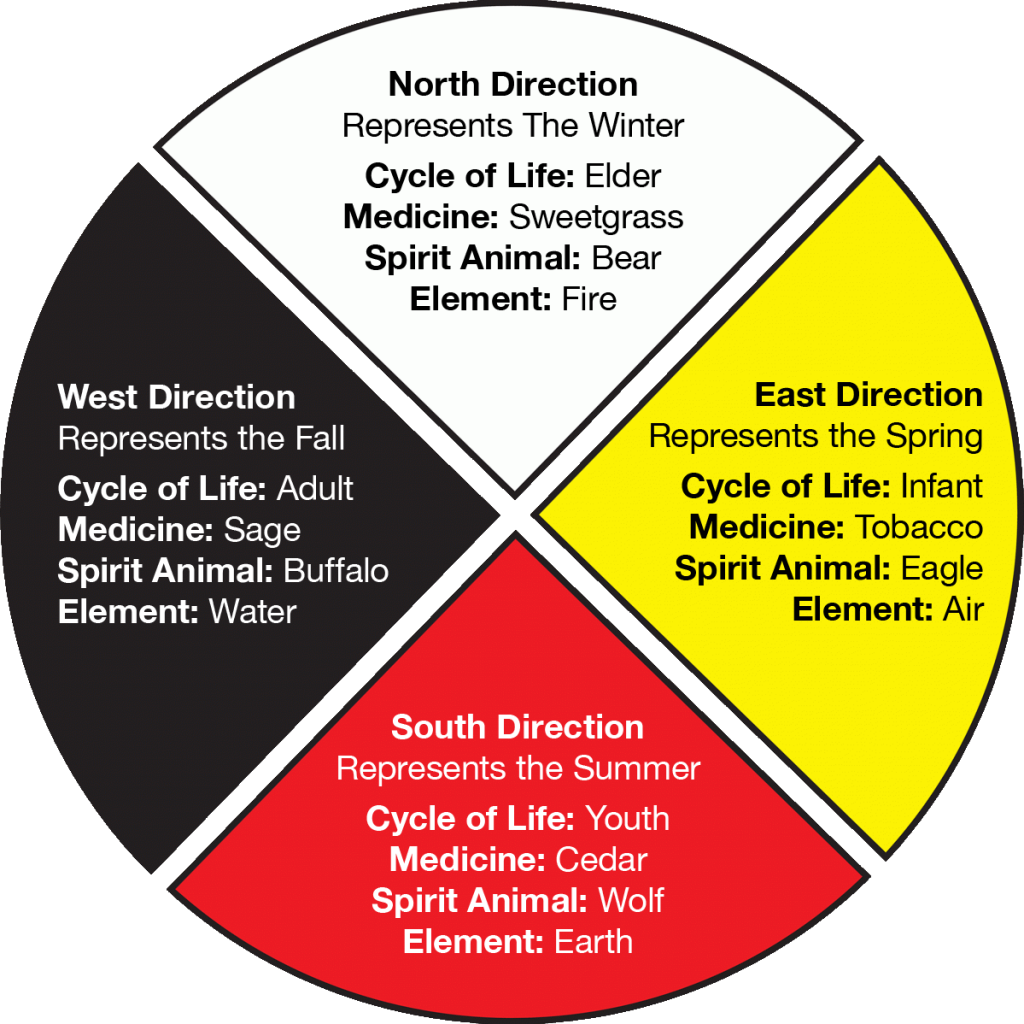

Cecil cites the medicine wheel to illustrate this holistic approach. “[You can] focus on the mental and emotional aspect of the medicine wheel, or the physical. How does it look at our spirituality? My question is not about the religion, but it’s about the spirituality which is medicine. Mental, emotional, physical, spiritual,” he says.

Photo Credit – Ojibway Medicine Wheel Teaching | Indigenous Domestic Violence Committee

Storytelling

First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples have a long and rich tradition of sharing stories and transferring knowledge through storytelling. Through storytelling, Elders and Knowledge Keepers help preserve the history, traditions and wisdom of their cultures; maintain spiritual connections; and reinforce connections to land and community. Stories are also at the heart of cultural experiences such as dance and ceremonies. In a learning setting, whether the setting is for ECE students or children in a child care setting, storytelling is a key tool for education and passing down Indigenous ways of knowing from one generation to the next.

Since students at FNTI come from all Indigenous cultures, FNTI’s teaching staff make space for storytelling by all. Cultural advisors and Instructors will share stories from their own cultural ways of knowing and being, and invite students to share their own stories and teachings as well.

Land-based Learning: ME (Mother Earth)

Land is sacred and deeply significant, representing a connection to one’s identity, community, and the past, present and future. Land-based learning encompasses much more than outdoor education. It emphasizes Indigenous worldviews and ways of knowing, acknowledging the interconnectedness of life and the importance of land in human existence. Land is central to Indigenous teachings.

“Our way, our Indigenous way, is very important – there is power in land. And land gives us the power to do a lot of things,” says Cecil. “To think about what comes from the Earth – everything comes from the Earth.”

As a Cultural Advisor and Elder, when Cecil asks children about “who they are,” there is a connection to land. He asks them to contemplate:

- Where do I come from? Not your address…

- Who am I? Not your name, but who are you?

- What is my purpose? There is a purpose for everything and everybody.

- Where am I going?

“It’s holding up something that we walked with. On our walk, we picked up a chunk of driftwood and brought it back and asked, what does this look like to you? That’s land-based education. Remember that oak tree we stood under? Then you draw the picture. And that’s for you. You don’t read into it, you just look at it and say, wow, what learning you have,” says Cecil. “When they can say who they are and tell me the whole story of where they came from, what they’re doing here and where they want to go while sitting in circle, we are also holding up something in our discussions and not reading from a book.”

Building Relationships: Family is community

Relationships are key in all Indigenous cultures. The concept of family goes well beyond Mom, Dad, Brother, Sister. It includes Elders, Grandmas and Grandpas, Aunties and Uncles, cousins and neighbours. Everyone plays a role in fostering the well-being and rearing of children. Relationships begin from birth and include relations with all that exists on Mother Earth that provides care and necessitates care – from land, nature and animals to family and community. Across Indigenous traditions, it is said that a child’s spirit chooses their parents even before entering the womb.

“The Grandmothers and Grandfathers, Aunties and Uncles who volunteer means more than volunteering services. It’s the connection we make with community,” says Cecil. “Maybe we can start to see those little individuals as human beings that are going to be adults someday. They’re going to be our future someday. We are responsible for them. As we say, it takes a whole community to raise a child. It takes a whole nation to raise a community.”

Learning more: How RECEs can expand their awareness and understanding of Indigenous knowledge and culture

Learning about Indigenous culture necessitates respect, transparency, a willingness to develop relationships and a commitment to gradually foster relationships. Each Indigenous community possesses a unique connection to their land, Elders, and ancestral wisdom, which shapes their identity.

Significant engagement often involves attentive listening, collaborating on initiatives, and ensuring that Indigenous perspectives are acknowledged and appreciated.

Erin Moe, Academic Dean, Partner Programs at FNTI, and Dr. Jennifer Davis, Assistant Professor, Queen’s University, shared the following recommendations for how RECEs may promote their understanding of Indigenous culture and build relationships:

- RECEs are urged to familiarize themselves with their local Indigenous communities and can also reach out to Indigenous families within their centres, and inquire if they might be willing to share their knowledge, understanding and teachings with staff and learners.

- Establishing connections with local communities requires time and effort. Engaging with Knowledge Keepers by connecting with local Indigenous organizations can facilitate access to training opportunities through workshops and programs.

- RECEs are encouraged to actively participate in the local events such as pow wows, or enrol in activities like beading and language classes, to begin fostering a relationship with nearby Indigenous Centres. It is important to note that many local Indigenous Centres are not exclusively available to Indigenous community members.

The journey begins with self-awareness and a genuine openness to listen and learn.

__________________

Acknowledgements

The College gratefully acknowledges the contributions of Cecil E. Isaac Jr., Cultural Advisor, Partner Programs, First Nations Technical Institute; Erin Moe, Academic Dean, Partner Programs, First Nations Technical Institute; Dr. Jennifer Davis, Assistant Professor, Queen’s University, and Elder Deb St. Amant, Elder-in-Residence, Queen’s University who generously shared their time, expertise and lived experiences with us so that we could further our learning in Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

Additional sources

- The Land is our Identity by Raechel Wastesicoot

- First Nations Pedagogy Online Project

- Reclaiming Education: Indigenous Control of Indigenous Education by Lateisha Ugwuegbula, Social Connectedness Fellow 2020, Samuel Centre for Social Connectedness in Partnership with the Misipawistik Cree Nation

- Ojibway Medicine Wheel Teaching